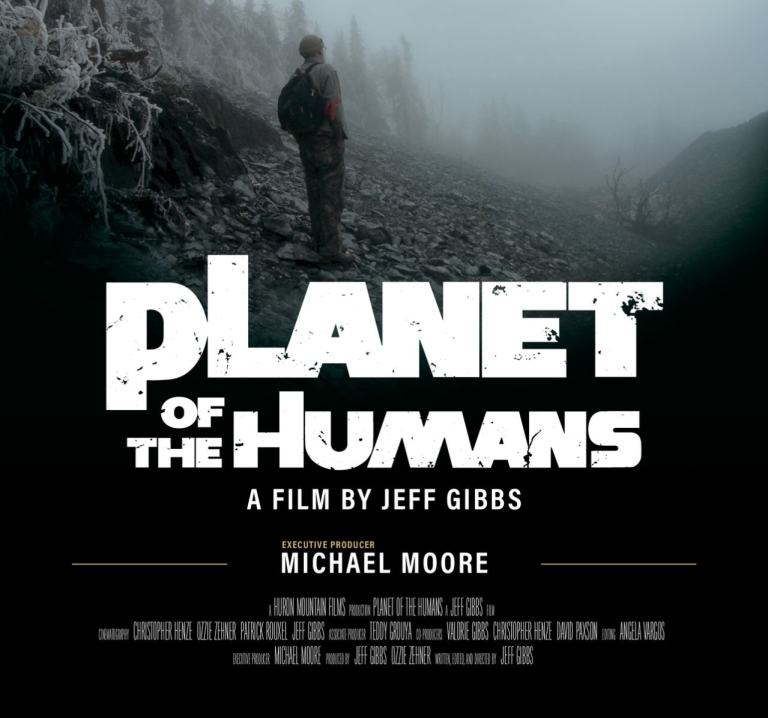

Writer-producer-director Jeff Gibbs is seemingly a grizzled veteran of an anti-capitalist eco-warrior, a self-professed “tree hugger” (with photographic evidence to prove it) and – given what we all know about the temperaments and tenacities that such people usually have – a man of courage to put such effort into calling out his own brethren in the environmental movement as it has manifested in the 21st Century. The release and reception of his controversial 2019 documentary “Planet of the Humans” has turned out almost completely as one might expect from a large special interest group who are particularly ineffective at dealing with criticism and scepticism.

It may be that the film would not have been picked up by the public in the way it was without the executive producer role of Michael Moore, which ultimately first generated the media attention and controversy. Conversely, there are certain notorious examples of documentaries (or books or articles or media personalities), however small or large their marketing budget, that have gained controversial traction in the mainstream primarily by virtue of the shots taken by them at widely accepted progressive wisdom. The example of Cassie Jaye’s 2016 feminism-sceptic documentary The Red Pill springs to mind; being one of the most talked-about documentaries of the last five years whilst otherwise maintaining a modest budget. The extremely brisk rise to fame that Jordan Peterson found himself in over his criticism of legally-enforced usage of ‘unconventional’ third-person pronouns, several years before he was publishing and promoting a book.

But I digress.

The film is overall an assessment, between ten and twenty years down the line, of the finer details of the large-scale corporate-and-state-backed environmental movements of the 21st century that were first set in motion by the whims of Al Gore and his ‘inconvenient truths’ and then activated by Barack Obama and his stimulus spending programs for green energy and green technology after his 2008 election victory. Gibbs does an effective job of highlighting the rank hypocrisies of those pushing harder for various “green” projects which, upon the slightest further inspection, can be shown to have their own environmental detriments in other realms. The deforestation and destruction of desert vegetation required to make room for solar farms and windfarms. The highly pollutive and energy-consuming processes used in the manufacturing of green technology, giving corporate executives a justification to deceptively claim that they champion green energy (with particular shots taken at Apple and Tesla). The highly deceptive portrayals of biofuel projects as “green” when it does little more than replace the combustion of fossil fuels with trees. These are just a few examples, but my personal favourite has to be the laying bare of Al Gore to his astonishing hypocrisies; the most effective of which being the clips of Gore lobbying congress on behalf of “renewable” ethanol fuel corporations very effectively juxtaposed with clips of rural communities in Brazil having their homes destroyed to make room for sugarcane cultivation.

There is clever usage of music in the film too. Different styles and textures to either compliment or deliberately ironically contrast the visuals at a given time. A particular musical high-point is the usage of Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s “The Enemy God Dances with the Black Spirits” which manages to simultaneously compliment the dramatic ferocity and resonate the irony in the accompanying video clips of all the notably un-green and ethically suspect industrial processes involved in the manufacturing of “green tech” such as electric cars, wind turbines and solar panels.

I challenge any viewer of this film to come away from it without ever taking the aspirational superficialities of corporate and governmental green projects with a generous pinch of salt ever again.

It is subsequently strange how, in the mainstream reactions to the film, particularly from environmentally-active people themselves, the film generated such controversy and ferocity. A particularly childish reaction in Vox portrays the content of the film as playing host to spiritual evil, under the guise of a scholar’s concern over “misinformation” (a common contemporary liberal heresy these days). It also supports censorship and deplatforming of the film and even goes so far as to say there are just too many “white men” amongst the scientists and academics interviewed in it. Another commentary on the film published in the Yale Climate Connections (yes, that Yale) goes as far as to call it “the most dangerous form of climate denial” and also feels the necessity to mention “white men” too. Gibbs is accused of “lazy privilege” and being “inflicted with the Dunning Kruger effect” in another review (which yet again feels the need to mention “white men”), another declared that “it ignores the solution of holding power to account and sounds like a racist dog whistle” (and yes, “white men” do not go unpunished!)

One more intriguing review is by Guardian darling and one of the most prominent environmental busybodies in the world, George Monboit. He, along with the other reviews mentioned above, appears to have to rely a lot on criticisms of the film that he knows in the current social climate will resonate the most reinforcement from readers; such as trying as best he can to link the film with “the far right” and how the film perpetuates racism.

It is worth mentioning how the film overall is somewhat unrefined in its precise scientific rigour and has received some valid criticism on that front. Most of the above reviews do indeed take ‘the science’ to task in the film and they do so with a large degree of emotional and righteous vigour. It is also correct to criticise the film’s scaremongering of overpopulation and the idea that no other option is available than to return to more primitive pre-industrial living.

However, most of the critics seem to be misrepresenting Gibbs’ real attitude towards renewable energy sources. He is, in truth, merely critiquing the fast-paced and unsustainable rate at which they are being commissioned and developed and the negative off-shoots that are so clearly resulting from that.

What many of these critics seem to also overlook is that the film is primarily about politics and perceptions of power imbalance and is not making any attempts to strongly flex any muscles of immaculate scientific accuracy. It is all very well for critics of the film lay bare its scientific flaws, but these are the same believers in the green technology revolution have themselves been overstepping the boundaries of science in their advocacy and have felt the need to utilise quasi-religious rhetoric of moral damnation on human consumption in the industrial age to get their point across. However, neither should Gibbs or his critics be significantly lambasted for this. Man naturally navigates the world with narrative and story-telling. Certainly, human civilisations have made great strides in the last thousand years in developing methods of knowledge creation that try to the best of their ability to present truth unadulterated by personal bias, fiction and idealism, particularly in the realm of science. But this fundamental tenet of the human mind to still have its attention resonated and aroused by cultivated narrative can never be eradicated. People know this full well, but they are rarely honest about it, or they maybe do not in fact even know they are doing it. Those wanting to inform the world about scientific evidence of anthropogenic damage to the environment felt the need to find a way to effectually inform very large numbers of people in a short space of time. Consciously or unconsciously, they employed (to a varying degree of extents) a quasi-religious apocalyptic narrative because it was obvious that it would be the most effective mechanism. The above mentioned critiques of Gibbs’ film could quite easily have each utterance of the word “misinformation” with “heresy” or “misleading” with “ungodly”. But it is not just quasi-religious narratives of climate change that are employed, but the type of narrative employed can be dependent on the type of person making the case. Those in the academies, in governments and in corporate “NGO” entities will be much less inclined towards a politicised narrative of climate change because even they are smart enough to suspect the potential irony of it, as people who could be easily considered as wielding institutional influence themselves. The Gores and the Obamas of the world can employ a mostly quasi-religious rhetoric to avoid this irony whilst the humble tree-hugging working class opinion-havers – such as Gibbs – are in a more useful position to employ a political one.

Given this primarily political narrative of the film, I found myself having these involuntary reminders while watching it of how all manner of “grass roots” progressive activist causes in general can easily find themselves being strongly invested in – or even fully adopted – by high corporate entities which might eventually be considered detrimental to the progressive cause in question in its initial state and intention. It is easy to sense the annoyance in Gibbs, as a tree hugging leftist and one who “lives off the land” and attempts to make his life as de-industrialised as possible, that such large corporate entities are singing his tunes. Similar sentiment to Gibbs’ can be sensed from certain sects of LGBT activism or feminist activism or anti-racist activism as they witness the adopting of their narratives by large corporate bodies, liberal politicians and international NGOs. Given that many of these progressive movements started out as part of the New Left in the 1960s, seeing themselves as combatting the cultural tenets and social offshoots of the capitalist power structure, it isn’t too difficult to put yourself in their shoes as far as you’d see how annoying it must be for them. It is as if capitalism is viciously taunting them. And, of course, we have reached the absolute pinnacle of progressive corporatism with the Canadian athletic apparel retailer Lululemon Athletica (with yearly profits of around 650 million dollars) recently putting out a marketing campaign involving a workshop which had amongst its stated aims “Decolonize Gender … unveil historical erasure and resist capitalism.”

However, all of these corporate activist pantomimes are usually temporary and seasonal, only really responding to the whims of popular culture in a given time and it is likely they will soon gradually fade away over the course of the new decade. Despite that, it will still leave a trace in the government policy and new corporate protocol that has been implemented as a result of the peak of the hype, less easily overturned. And the more long-lasting traces will likely be in the realm of environmental activism.

I don’t agree with Gibbs’ fundamental worldview and politics, but it has been very helpful for such a figure as him to come along and allow the reality of the mechanisms and conflicts of social narratives that dominates most climate activism to be made clear. It will never be that the ultimate problems of anthropogenic environmental problems, when and where they truly exist, will be solved without narrative (though obviously not so much that there is no room for science), and we have to subsequently decide which narrative to employ that will be most successful in their outcomes for all parties concerned, and not just the academics, politicians and self-righteous NGO employees.